How our Identities Create Conflict

“A man has as many social selves as there are individuals who recognize him.” — William James, The Principles of Psychology

In my practice my clients learn quickly that arguments are usually more complicated than they initially seem. After sharing a heated argument they had earlier that day they ask, “Who was right?” It’s not that simple.

What is Identity?

Identities are the internalized meanings and expectations of one’s roles (e.g. parent, student, designer, therapist, coach) and social group memberships (e.g. African-American, female, Agnostic, foodie). Identities are also connected to our traits and characteristics (e.g. good person, blonde, redhead, tall, athletic, smart). We can have many identities, yet only one or two will be present at a time.

For example, when talking to a male friend, my identity as a “good friend” may be present. My other identities such as sister, daughter, psychotherapist, artist may not be present. However, when my friend begins to talk about his female partner and how she can be so “irrational”, my identity as a woman may come to the forefront.

Identities are the internalized meanings and expectations of one’s characteristics (e.g. I’m a good person), roles (e.g. parent, student, designer, therapist, coach), and social group memberships (e.g. African-American, female, Agnostic, foodie).

As you can imagine I might become agitated by his statement. For one, “irrational” is a negative stereotype given to women in our culture. I might respond to his statement unconsciously, snapping back, “Well, maybe she has something to be angry about!” Or, I could explore the layers of identity that are in conflict and address each layer, giving myself the opportunity to respond more skillfully and avoid an unproductive argument.

Levels of Identity

In my practice, teaching, and in life I have found it tremendously helpful to identify 4 levels of identity when finding myself in conflict with someone. Not only does it help me understand where we are in conflict, it also gives me an idea of how to repair the rupture in our communication and relationship.

Four levels of identity:

Intrapersonal

This level is about the parts of ourselves that interact with each other; our inner dialogue. For example we may make a commitment to ourselves to exercise 30 minutes every day. After a few days we start skipping out. Our self-talk might include a judging part saying, “See! You can’t stick to anything. You’re worthless.” Another part might feel hopeless saying, “Yeah, you’re right, I can’t do anything right.” Then, another cheerleading part might step in and say, “Tomorrow, we’ll start again. We can do it!”

As in the film, Inside Out, these parts of ourselves can go to war with each other and we can collapse from the conflict or develop avoidant behaviors.

Interpersonal

The interpersonal level deals with our identity as it relates to one-on-one relationships. For example, Sheela sees herself as a “good” person. She decides to stay late at work to help an employee with a distressing personal problem. She arrives home to her family later than usual. Her wife is angry and calls her a “selfish” person for putting her needs before the family’s. This threatens her identity as a “good” person and she will likely feel the need to protect this important positive identity.

As you can imagine the argument could proceed with Sheela telling her wife that she’s not selfish, that she was being supportive to an employee in need. Her wife, still upset that her partner is prioritizing work relationships over the family continues to call Sheela “selfish.” The conversation is now stuck and the tension can only get worse.

As you can imagine the argument could proceed with Sheela telling her wife that she’s not selfish, that she was being supportive to an employee in need. Her wife, still upset that her partner is prioritizing work relationships over the family continues to call Sheela “selfish.” The conversation is now stuck and the tension can only get worse.

Instead, Sheela’s wife could say something like, “When you stay late at work without letting me know beforehand, I feel irritated and neglected.” By sticking to what actually happened (i.e. Sheela stayed late at work without informing her wife) and expressing her feelings rather than acting them out by name calling, Sheela’s wife is speaking in a non-defensive way. This gives Sheela the space to also respond non-defensively. (For more about this check out Non-Violent Communication and the article Essential Tools for Navigating Difficult Relationships).

By sticking to what actually happened (i.e. Sheela stayed late at work without informing her wife) and expressing her feelings rather than acting them out by name calling, Sheela’s wife is speaking in a non-defensive way.

Intergroup

The intergroup level is less often discussed and yet is one of the most influential. Because not all groups have equal social privilege, groups can easily come into tension with each other. When this happens our sense of who we are (i.e. sense of self) can become merged with one of our group identities.

Because not all groups have equal social privilege, groups can easily come into tension with each other. When this happens our sense of who we are (i.e. sense of self) can become merged with one of our group identities.

Group identities include social groups like gender, race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, religion, socio-economic status, or generation, as well as groups like “foodies” or “world travelers.” They also include roles like parent, student, teacher, child, CEO, employee, farmer, etc.

There are emotionally charged ideas, histories, stereotypes, and assumptions around any group identity. When these group identities come to the forefront in conversation, people can easily take them on as personal. Once this happens, the conversation is no longer between two individuals, but rather two groups. We put on the uniform of the group and lose the empathy that comes with engaging as two unique people. We speak and fight as combatants for a group of people or ideas who are not present.

We put on the uniform of the group and lose the empathy that comes with engaging as two unique people. We speak and fight as combatants for a group of people or ideas who are not present.

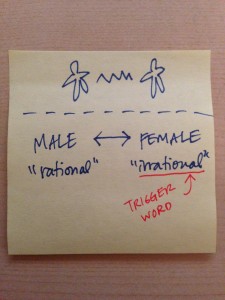

In the first example, I could have become solely identified with my identity as a woman and forgotten I was talking to my friend—seeing him only as a member of a group of sexist men. In that case, the word “irrational,” attached to the negative cultural stereotype for women, would have been the trigger.

In the first example, I could have become solely identified with my identity as a woman and forgotten I was talking to my friend—seeing him only as a member of a group of sexist men. In that case, the word “irrational,” attached to the negative cultural stereotype for women, would have been the trigger.

(Incidentally these negative stereotypes and associated trigger words come from our culture (TV, movies, news) and are learned as we are socialized as children. For more on the impact of negative cultural stereotypes check out the article How Unconscious Bias Manifests.)

As an alternative to being triggered and lashing out from my group identity, I could name the cultural tension by saying, “Sounds like you’re really upset at your girlfriend and she’s behaving in a way that doesn’t make sense to you. However, I’m feeling a little defensive when you use the word ‘irrational’. That word is a common negative stereotype for women.”

Transpersonal/Archetypal

The fourth level addresses levels of identity that are beyond the personal, or what is called “transpersonal.” C. G. Jung called this level the collective unconscious and the elements at this level he named archetypes. Some archetypes that can appear are: Hero, Villian, Mother, Father, Child, Trickster, Orphan, Shadow. In the example of me and my friend, the trigger word “irrational” invoked the Victim vs. Persecutor dynamic. Somewhat unconsciously, the polarizing archetypal energies of myself as Victim and my friend as Persecutor emerged into our dynamic. For more on this check out Karpman’s Drama Triangle.

Next Steps

By knowing the different aspects of identity, we can navigate complex conversations with more agility and presence. How do you see applying this to your life?

Exercise: Self-Reflection

Reflect back on a conflict you had recently:

- Where were you talking from? Were you talking from the group level or the personal level?

- Which of your identities were activated by the person you were talking to? (e.g. woman, man, friend)

- Which parts of you were activated (e.g. a judging part of you saying “you don’t know what you’re saying”, or a scared part that just wants to flee).

- What sensations, emotions, or thoughts did you notice?

- What will you do differently based on what you learned from this exercise?

As you can imagine one can get really activated in these dynamics, especially when dealing with conflict that is close to the heart of one’s identity like gender or race. Self-regulation—one of the elements of emotional intelligence—is an essential skill.

Resources

Devos, T., Huynh, Q.-L., & Banaji, M. R. (2012). Implicit self and identity. In M. R. Leary & J. P. Tangney (Eds.). In Handbook of self and identity (pp. 155-179). New York: Guilford.

Oyserman, D., Elmore, K., & Smith, G. (2012). Self, self-concept, and identity. In M. R. Leary & J. P. Tangney (Eds.), Handbook of self and identity (pp. 69-104). New York: Guilford.

Singer, T. (2010). The transcendent function and cultural complexes: A working hypothesis. Journal of Analytical Psychology , 55, 234-240.

Previous Post

Previous Post Next Post

Next Post